On April 10th 1545 the Spanish founded the settlement of Villa Imperial de Carlos V. It lies at the foot of Cerro Potosi which is nicknamed “Rich Mountain”. The Spanish found Silver Ore and it is said the entire mountain is made of silver. Within 30 years the City of Potosi was the largest city in the new world. At the peak of its production in the latter half of the 16th Century Potosi was producing 60% of all the silver mined in the world.

The Spanish constructed a mint and produced the eight real silver coin also known as the Spanish Dollar, a Peso, or most famously “Pieces of Eight”.

Silver flowed out of Potosi in three main directions. Some went down the River Plate to Buenos Aires and across the Atlantic to Spain. Most was packed on trains of mules and llamas and taken to the Pacific Coast. From there some was sailed to Panama City where it was loaded back onto mules for the crossing of the Isthmus of Panama to the town of Portobello. There it was loaded onto the Atlantic Treasure Ships, so beloved of British, French and Dutch privateers and pirates. So much silver flowed into Spain that the world value of silver was depreciated.

Even more of the Silver moved in the opposite direction. In Acapulco, Mexico the silver was loaded onto the Manilla treasure fleet bound for the Spanish Phillipines. Asia was the target for much of the silver because most Asians had no interest in European goods. They were selling tea, silk, ceramics and most importantly spices. They wanted silver to pay for these goods.

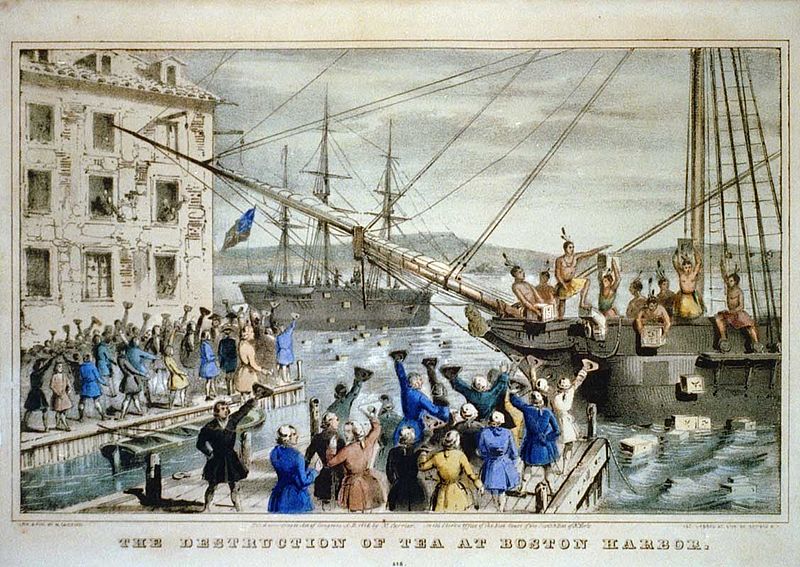

The Spaniards had silver to spare, but for other nations silver was a problem. The Dutch, the Portuguese, French and English developed elaborate trade systems to acquire silver in asia sufficient to fill their holds with precious spices. For example the Dutch invented the Amsterdam stock exchange to raise funds and founded the East India Company. The company built factories to process goods from the far east. They smuggled tea into England, breaking the British East India Company monopoly, kicking off the Anglo-Dutch Wars. They also broke the English monopoly in the Americas. The Boston Tea Party was significantly part of this struggle.

A Dutch ship, carrying what silver it could raise in Europe, and whatever goods might sell along the way, would sail to Asia via the Cape of Good Hope, offloading manufactured goods in exchange for fresh food and Cape made wine. They might pick up cotton and timber in India. They could sell this in the Spice Islands and pick up some spices, but not enough to fill a ship. They needed to make their silver go further. So they brought spices to China which they exchanged for tea, silks and ceramics. They took these to Japan where they could sell them in Nagasaki in exchange for silver. They could bring Japanese goods back to the spice islands and increase their stock of silver until they could fill a ship with tea, spice, silk and porcelain.

Dutch traders had to figure out what they could manufacture or trade to the Spaniards who had so much of the necessary silver. The flow of silver out of Europe was so one directional that some economies refused to permit its export. The Dutch took over the Island of Taiwan from the Spanish and turned it into the export economy of Dutch Formosa. They imported Chinese workers to farm cash crops and treated them as little more than slaves. The goal was to get more silver from China. They repeated the exercise with some of the small islands that grew nutmeg and cloves. In Sri-Lanka they brokered a deal with the native king to expel the British, in exchage for access to cinnamon.

The English developed other solutions to the silver problem. They stole tea plants from the Chinese and set up their own tea plantations in Assam and Darjeeling in India. Around Calcutta (modern Kolkata) they established Opium Poppy farming. The processed opium was smuggled into China in exchage for silver. The silver was the brought to the Pearl River where the Europeans were restricted to a single trade entry point in Canton. The Chinese attempted to put an end to the Opium smuggling and this resulted in the Opium Wars.

By the 19th Century Europe simply did not have sufficient silver to maintain the one sided trade relationship imposed by Qing China. Ultimately the Chinese refusal to engage in open trade with European powers resulted in the demise of China as a world power. So, strangely, the foundation of a small settlement at the foot of a Bolivian Mountain led in a roundabout way to the demise of Imperial China.

-=o0o=-

This site is available for free and I make no money from any ads you see here. If you would like to show your appreciation feel free to leave a comment or you can buy me a coffee! http://buymeacoffee.com/DonalClancy